BIS has recently published a new report to the G20 about options for access to and interoperability of CBDCs for cross-border payments. The report presents different options for access to and interoperability of CBDC systems to facilitate cross-border payments. It assesses these options based on five criteria: do no harm, enhance efficiency, increase resilience, assuring coexistence and interoperability with non-CBDC systems, and enhance financial inclusion.

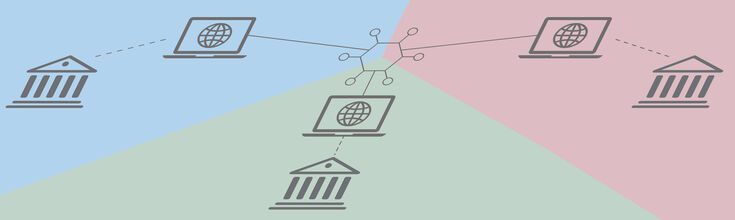

When identifying access options, the report distinguishes between, on the one hand, access by foreign banks and other payment service providers (PSPs) to wholesale CBDC (wCBDC) systems and retail CBDC (rCBDC) systems in the case of a two-tier model, and, on the other hand, access to rCBDCs by non-residents. Access by PSPs may be indirect (ie via an intermediary) or direct (ie without an intermediary). These models are similar to the access models of traditional payment systems as discussed in BB 10 of the G20 cross-border payments program (CPMI (2022b)). In a third model – closed access – only domestic PSPs are granted access to the CBDC system. The discussion on access to rCBDCs by non-residents focuses on whether and under what conditions (eg transaction and holding fees and limits) non-residents are granted access.

There is no “one size fits all” model for access to and interoperability of CBDC systems. For example, while compatibility might be the least costly form of interoperability, it may not achieve similar efficiency benefits to multiple interlinking systems or developing a single system. Combining compatibility with a direct access model would go a long way, but given the challenges of achieving direct access, such a solution might be difficult to realize in the short run. Similarly, while interlinking via a single access point may not necessarily require direct access or the establishment of new technical components, it has scalability limitations. Overall, interlinking of CBDC systems through a hub and spoke or single system might bring more improvement to the cross-border payments market than compatibility or single access points. The same holds for direct access models compared to closed or indirect access. Yet, given the elevated challenges of these solutions, they are most likely to be implemented where the benefits of enhanced cross-border payments exceed the challenges, such as between countries with large trade volumes, or between countries with similar CBDC objectives and designs. This inherently might entail the risk that the interoperability and access models with the highest potential to alleviate current cross-border payment frictions are not implemented for the use cases currently heavily impacted by these frictions, such as remittances.

For full report: https://www.bis.org/publ/othp52.htm